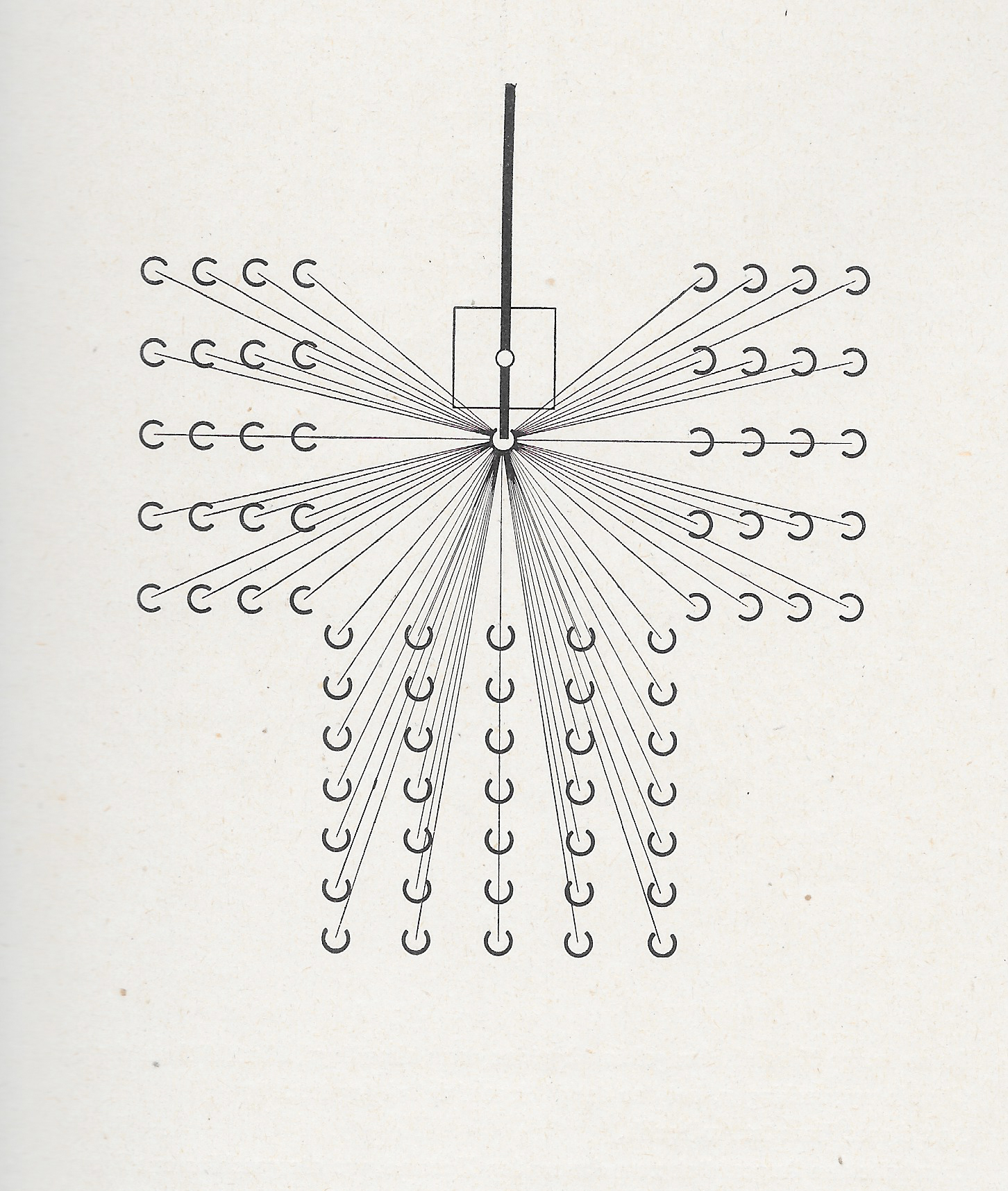

Heiliger Aufbruch (The open Ring) (fig 1)

The Ring breaks open (1). Those gathered around the altar understand that they are on a mission, a journey to their true homeland (Heimat) and so the intimate Ring “… opens from the heart of the Lord (Son) and from there opens wide to the Father.”(2) The symbolism of the open Ring is made more explicit when one remembers that when Schwarz wrote, the priest would have stood facing the altar and thus looking toward the way that opens to the journey. Having been fed at the table, the people are now ready to follow Christ to the Father.

Schwarz references the example of Leonardo daVinci’s Last Supper in support of this plan. Christ is in the center, surrounded by his Apostles to the sides and ends of the long table. Christ himself looks out into the open space in front of the table. Now the circle of intimacy is no longer closed, but open to the radiant light. The open quarter becomes a gateway or window revealing the Way on which the Faithful are called to follow and for which the Eucharist is both strength and support.

The presiding priest is positioned facing (liturgical) East in Schwarz’s conception. But the priest is not distanced from the intimate gathering of God’s People. He presides and leads, but is equally and distinctively a member of the gathered community. Furthermore, the altar becomes, not the true source of the radiance of God’s light, but rather that sacred place where God’s people encounter the Divine light. It is here that, leaving the world behind, the Church sees its true form as a People in which Grace is active to heal that same world (3).

To some degree, one can see a precursor to this arrangement in the antiphonal choral arrangement of medieval cathedral and monastic churches. (Fig 2-3) Although Schwarz proposes that historic churches can be exemplars of this concept by placing the altar at the crossing with the people arranged in the nave and transepts (fig. 4), the best examples of this arrangement are more contemporary. (Fig. 4-8. See notes on each image).

It is notable that, writing in 1938, Schwarz envisions that these plans would make use of the ad orientam position of the priest (4). Indeed, St. Albert’s in Saarbruecken, Germany, (fig. 4) was build according to this arrangement (it was later adapted to liturgical changes after Vatican II). Although ad orientam can be seen as more fitting for the theology expressed in this design, the current ad populum position need not detract from the sense of openness to divine light and preparation for the journey. In some respects, it actually could enhance the symbolism of the priest’s role as alter Christus, something of significance in the liturgical understanding of the Council of Trent.

The caveat with the Open Ring is the temptation to be reduced to the model of Greek theater. Although ancient Greco-Roman theater had elements of religious function, it was decidedly not appropriate for Christian liturgical theology. Here lies a challenge of this design: a society accustomed to stage and theater productions can begin to see itself in terms of ‘audience’ and the liturgy as ‘performance’. This challenge presented itself even in “traditional” liturgical usage, an unfortunate manifestation of worldly culture insinuating itself into Christian practice.

(1) Schwarz, Rudolf, Zum Bau der Kirche, Verlag Lambert Schneider, Heidelberg, 1947. “Der Herr is wirklich in ihr, aber aus dem Herzen des Herrn heraus is sie weit zum Vater geoeffnet.” Schwarz, p. 46.

(2) Schwarz, p. 45

(3) Schwarz, p. 53 “Wenn die Menschen aus den weltlichen Zusammenhaengen in diese Kirche hinuebertreten, dann erleben sie ihre Geschictsform als Gestalt der wirkenden Gnade, den nauch die offene und winde Gestalt dieser Welt ist Heilig gemeint und erhalten.”

(4) Schwarz, p. 45