Heiliger Ring (The Ring, or Holy Intimacy)

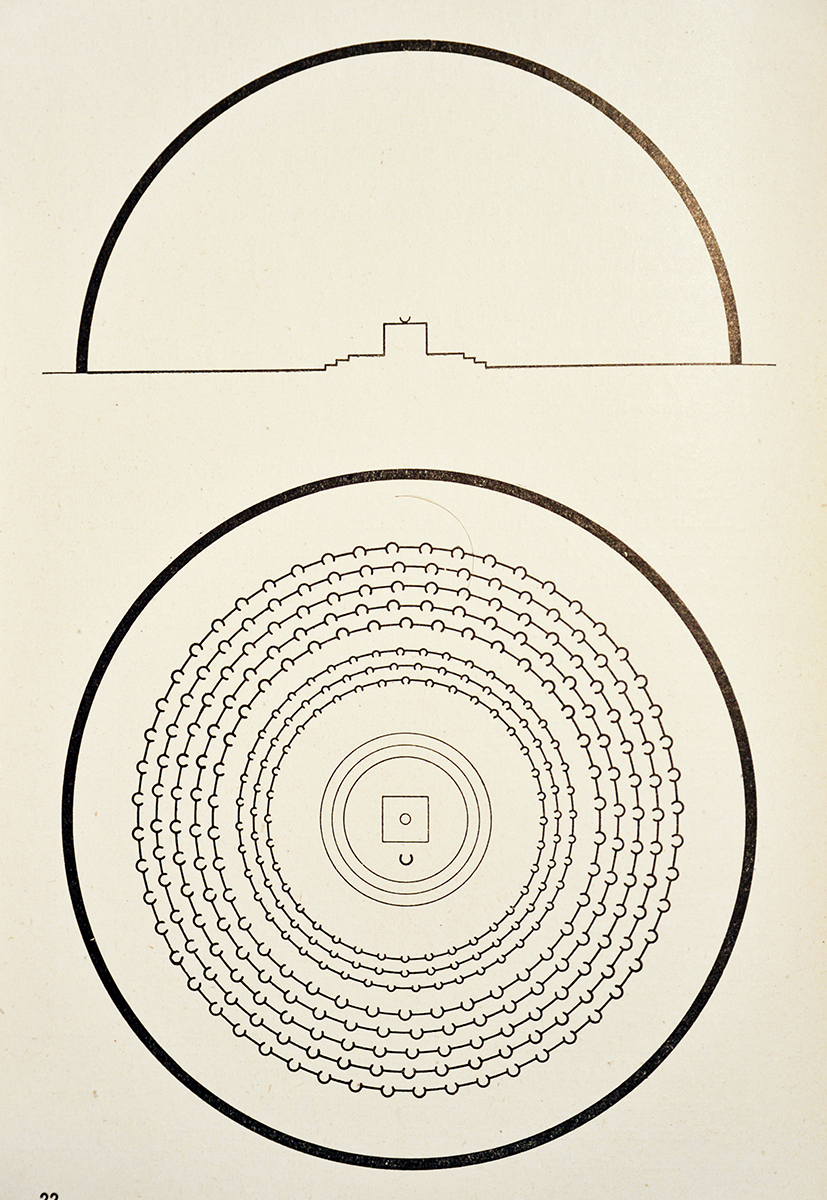

Schwarz begins the sequence of liturgical designs with a return to the beginning. As he says in Vom Bau der Kirche(1) “We must begin anew, and our new beginning must be authentic”. This new beginning (Anfang) is found in the intimacy of a small space, with the community gathered around the common table. Here, where ‘two or three are gathered in (Christ’s) name’ the Lord is present in the midst of his people. This, says Schwarz, is the simple and original form (einfache Urform) (2) of sacramental space. Those gathered, both young and old, stand around the table of the Lord’s Supper, itself a manifestation of Christ’s presence in the midst of humanity.

It is worth noting that the plan of Holy Intimacy (indeed centrally planned churches in general) also finds its origin in the ancient “martyrium” which itself is related to ancient mausoleums. From an early day, saints (generally martyrs) were held in veneration by the Christian faithful. In this sense the centrally planned structure has a connection to the emerging cult of saints (particularly martyrs) which flourished in the primitive Church and was given greater emphasis during and after the fourth century.

Liturgically and sacramentally, the Ring reflects a theology of intimacy and incarnational imminence. It is noteworthy that Schwarz’s models presume the Roman Missal of 1920, itself largely the Pian Missal of 1570. However, there is no issue here of the priest presiding ad orientam or adversus populi since those gathered encircle the altar. Furthermore, the Ritus servandus of the pre-Vatican II Missal indicates that even if the altar has a retable, the order of incensing is based on a free-standing altar. Directives were also included for just such a free-standing altar. Hence, Schwarz’s “Holy Intimacy” represented a worthy arrangement for the celebration of the Liturgy expressive of the Divine presence in and among the people of the Church.

An excellent ancient example of the Holy Intimacy plan is Santa Constanza in Rome (Fig 1). This fourth century church was originally intended as a mausoleum for Constantine’s daughter, Constantina. The mausoleum was converted for liturgical use in the thirteenth century by Pope Alexander IV (1254-61).

The current church was originally a mausoleum attached to a larger funerary basilica associated with the martyr St. Agnes. While the basilica no longer survives (remnants are visible) the mausoleum itself is largely well preserved and notable for its particularly ancient late Roman style mosaics in the ambulatory. (fig. 2)

These mosaics represent an interesting transitional period in early Christian art. Grape vines and harvest scenes have clear allusions to Gospel references to the Eucharist, particularly Christ as the ‘true vine’ and various parables and symbolic parallels with the vineyard and harvesting. Such themes were also a routine part of the artistic representations related to the wine-god Bacchus. We see here an example of early Christians ‘baptizing’ older pagan imagery to bring it into theological alignment with Faith in the ‘True God’.

The central well of the church is surrounded by twelve columns (fig. 3). These column support the clerestory drum which is crowned by the central dome (fig.4) (3).The altar is centered in the brightly lit well below the dome, an excellent example of Schwarz’s model. As can be seen today by the arrangement of chairs, the congregation surrounds the altar for Mass just as Schwarz envisioned. (fig. 5)

A modern example is that of the priory oratory at the Camoldolese hermitage in Big Sur, CA. This space reflects all of Schwarz’s principles just as its ancient predecessor (fig. 6) . The oratory forms the center of the entire complex of hermitages and monastic cells. The monastic austerity of the environment allows all attention to be focused on the altar, a symbol of Christ in the midst of his escatological family, and the liturgical action taking place upon it.

Another related example is the oratory at the Norbertine monastery in Albuquerque, New Mexico (fig 7). This oratory makes use of indigenous architectural forms – the kiva of the native peoples. Kivas served indigenous communities in the area as social and religious centers and its incorporation into the design of the monastery chapel recalls the same principles of adaptation represented in the mosaics of Sta. Constanza. The fabric work of liturgical artist Pamela T Hardiman filters light throughout the environment, focusing the space on the central altar, just as we have seen in our ancient example filters light throughout the environment, focusing the space on the central altar, just as we have seen in our ancient example.

Schwarz’s next model has its origins in the primordial theology of holy intimacy, but there is a notable development: the escatological family centered on the intimate presence of Christ in their midst becomes an open circle. This has significance which we shall explore in our next installment.

NOTES

1 - Schwarz, Rudolf, Vom Bau der Kirche, Druckerei Winter, Heidelberg, 1947, pg.21. “Wir muessen new anfangen und unser neuer Angang muss wahrhaftig sein.” Translation mine.

2 – Schwarz, pg. 21

3 – The dome fresco is of a much later period.