Historians – and people in general – divide time into eras, periods and movements. These are convenient parcels which allow us to study particular aspects of history and to “structure” our memory of events. But actual time is not so divided, and the passage from one period to the next is seldom so obvious as historical writings and study might suggest, particularly for those living it. True, there are defining moments, but ultimately these are part of a larger, unified continuity.

The story of St. Paul and his namesake basilica outside the walls of ancient Rome are good examples of this reality. Paul’s life is conveniently divided between the time before and after his conversion. But in reality, the seeds of that moment on the road to Damascus were planted and growing long before they burst forth in blinding illumination. Likewise, the grand basilica which today stands at the site of his execution and burial represents a continuity through history even as it has been marked by its own defining moments.

St. Augustine in his homily on the dedication of a church speaks of the church building as a metaphor for the living Church. This can be especially applied to St. Paul Outside the Walls. The Gospel of Luke and Book of Acts are uniquely related to St. Paul and his ministry. These two writings represent the continuity between the life, ministry, passion and resurrection of Christ and their continuation in the ministry of the Church. In the biblical canon, Acts is followed by the letters of Paul. Thus, Paul becomes another link in the chain from the Gospel, to Acts (which begins with St. Peter’s ministry) and on to the Church, even to our own day.

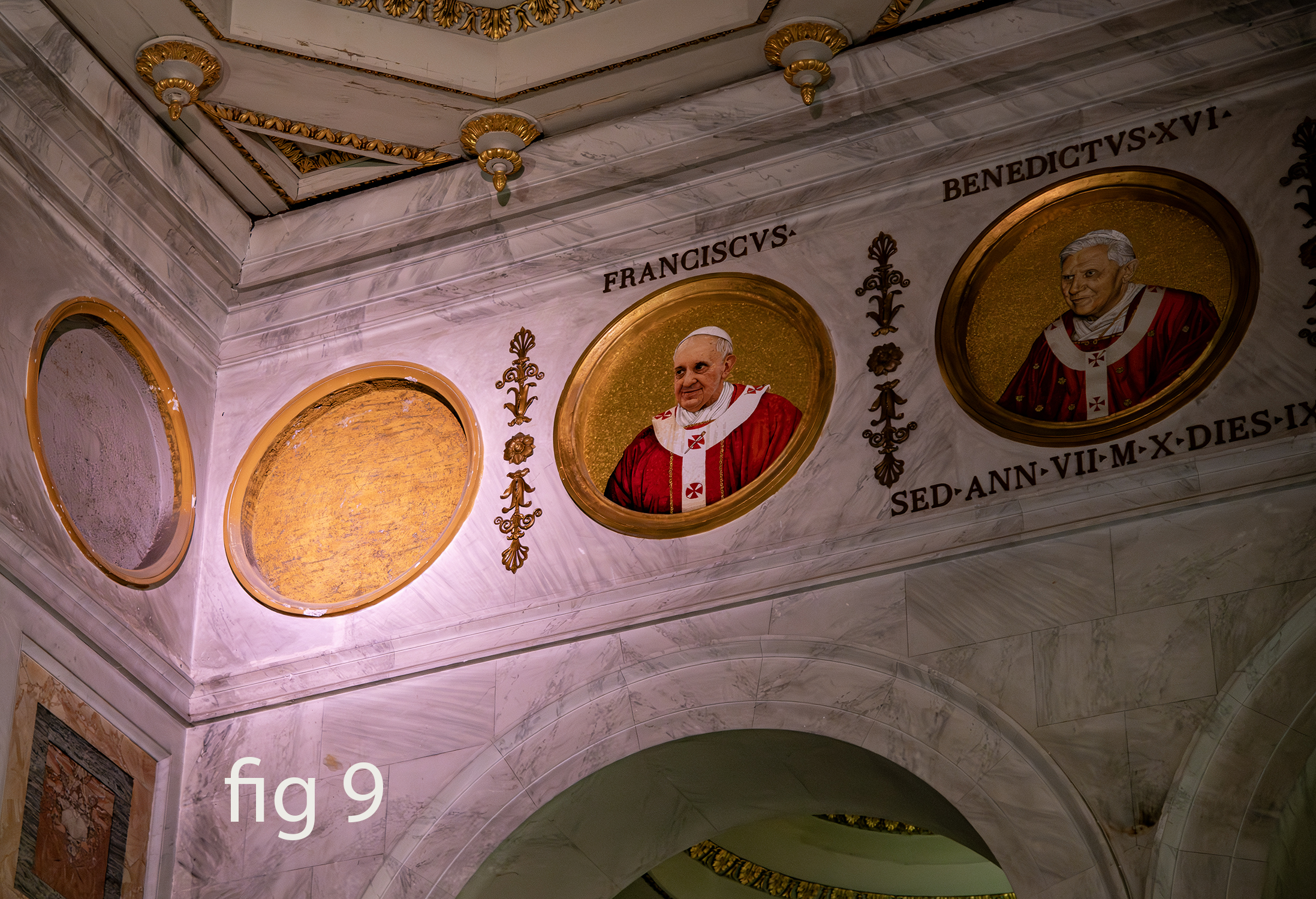

Several aspects of St. Paul Outside the Walls exemplify similar continuity. Unlike many of the other Roman churches, pews and chairs are absent in the great nave (fig. 5). The only seating is benches which are located in the transept behind the altar. The architecture, like most ancient churches, reveals the various changes in style over the millennia. Two aspects which are notable are the Gothic baldacchino by Arnolfo di Cambio (fig. 6) and the triumphal arch (fig 8). This latter feature is one of the few elements which survived the fire of 1823. Especially famous are the series of papal portraits in the frieze (fig. 9). These three are worth closer examination.

Arnolfo di Cambio (1245 – 1310?) represents the aesthetic transition from Gothic to the early Renaissance. His work was, at the time, both innovative and in continuity with the recent past. Gothic took on forms in Italy that departed from the more classic French style common north of the Alps. Cambio, Giotto, Cimabue and others were heirs to both this new style and the more traditional Roman influenced local architecture. They blended the two into the new and innovative style of the Renaissance. Looking at di Cambio’s baldacchino over the confessio in St. Paul’s (fig. 6) one is reminded how the Church has always embraced the new and innovative, even as it treasured it’s Tradition.

The great triumphal arch (fig. 8) links the pilgrim to an even earlier era, that of late antiquity and the Roman Empire. Triumphal arches were traditionally built in the Forum Valley to celebrate great military victories (arches could be constructed for other notable events, ranging from establishment of new colonies to the installation of a new emperor). The Arch of Titus and Constantine are particularly famous. In the case of particularly ancient churches such as St. Paul’s, the transition from the nave to sanctuary was marked by such an arch. In the iconography of the arch at St. Paul’s, Christ, the true Lord of all, presides over the cosmos, flanked by the twenty-four elders of Revelation and the four-winged creatures from Ezekiel (which also symbolize the Gospel writers). On the far sides Peter and Paul stand directing one’s gaze toward the glorious Pantocrator.

A similar continuity with ancient Roman symbolism is the enormous stand for the Paschal candle (fig. 7 and 7b). Scenes from the life of Christ are carved into this towering structure. It is thus reminiscent of the victory columns of antiquity such as Trajan’s famous column. Instead of a narrative of military victory, the paschal candle represents the victory of Christ over Death and the joyful hope of those being initiated by baptism into Christ’s Church.

The most explicit imagery of continuity, of course, are the series of papal portraits in the frieze surrounding the church (fig. 9). Apostolic Succession of the bishops, and for the West, especially the Bishop of Rome, has been a cornerstone of continuity with the Apostles since the late first century. The practice of installing portraits of the presiding Pope began with Pope Leo the Great (440-461) and continues to our own day. The portrait of the current pontiff is illuminated, but because of how recently he was elected, Pope Leo XIV is not yet depicted. While obviously, many of these portraits are somewhat fanciful, the 40 oldest did survive the fire of 1823. Thus, these portraits in particular represent a link to the art and traditions of the fourth and fifth centuries.

One may wonder why the papal portraits are at St. Paul’s and not St. Peter’s. In antiquity, the Bishop of Rome was described not as the successor of St. Peter alone, but as the successor of St. Peter AND St. Paul. In the Book of Acts, the Ascension of Christ is followed by the ministry of Peter, which then transitions to the ministry of Paul. Hence, Peter and Paul marked the transition from Christ to the Church. Paul’s mission to the gentiles was also significant in this regard.

Once again, we see a sacred environment which embraces the creative genius of every generation as well as the commitment to preservation of that which is most sacred. We also see how the faithful are invited to move through the space, through different aspects of entry, into the vast openness of the nave, through the triumphal arch to the altar and the heavenly realm. Notably, at least for the Holy Year, one departs a different way than one enters. Like the Magi in Luke’s Gospel or Paul on the road to Damascus, we ought to be changed by the encounter with Christ. Each Liturgy likewise ends with a Rite of admonitory sending. We who entered as individuals must go forth as one People, transformed in continuity with those who went before us, but also with those who come after.

With these things in mind, it was time to head back north and across the Tiber to our final destination: St. Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican.